LEAP #1 Media Memoir

Can Music Really Save a Life?

The first memories I have of creative media come to me as a child of about 5 years old, sitting on my basement stairs listening to my father, sometimes alone sometimes with his buddies making music. Occasionally I would be invited down to “jam” with them, adding my talent to the percussion. What 5 year old doesn’t love a tambourine? At this young age I didn’t know how important the songs of Glenn, Artie, Dizzy and the Count were to my dad and the others. But there were a few things I did know. I knew I wanted to play a real instrument myself someday and I knew my dad always had this strange way of answering people when they asked, “What do you do for a living?” His answer was always the same, “Music is my life, but I sell insurance to make a living.” I knew he loved music, but didn’t know until I was a bit older that he attributed music to actually saving his life.

The explanation of this “life saving” music came to me in bits and pieces during my adolescence, but it wasn’t until I was in my late twenties (you know that time period when your parents’ advice and stories start to make sense) that I was able to put the pieces together into a story that I have shared with my own children that even credits their existence to music.

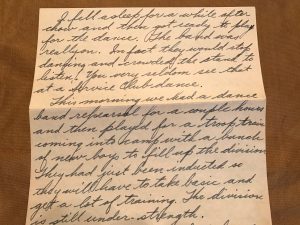

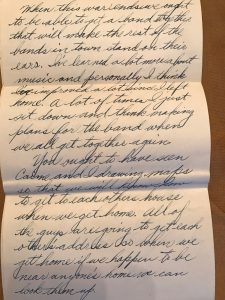

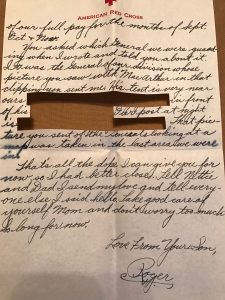

Even more of the story was made clear through letters written by dad to my grandmother on a weekly basis. My mother and I found these after doing some “attic cleaning.” What a treasure they proved to be.

This story starts with an 18 year old high school student who enlists in the army before even before graduation in 1942. This young man was my father, Roger.

Uniontown High School’s Orchestra, 1942

My dad told me he and his buddies couldn’t wait to enlist, especially after what had happened on December 7, 1941 of their senior year. In August, following graduation not only did my dad board a train headed for boot camp, but, as he put it, “so did most of the city.” His classmates, Bill Caton, Bill Miller, Dutch, Harold, and Clem joined him and with each of them they brought a musical instrument. Bill Caton brought a clarinet, Dutch a trombone. Harold, the other Bill, and my dad brought “horns.” Clem was a drummer so I’m not sure how that worked for him. They all had been members of the high school band and had even put together their own swing band that played in local clubs.

The train trip took them to Arkansas. I’m sure by now you’ve figured they passed the time by getting together and playing their music. That is the predictable part of what happened. The less predictable part involved an army Master Sargent who kept true to his word. As my dad told it, somewhere between Chicago and Little Rock, this Sgt. heard them play, wanted their names and said he would get them audiences for the Division Bands.

The next part of the story gets a little sketchy for me because my dad never wanted to emphasize the warfare part of his memories. I think he told it from a different perspective to help wash away some of things he witnessed. He actually made it sound as if they had a grand time at boot camp at least until their training was finished and the guys were split up. Harold and my dad went on to Oregon and from there, to the Pacific theater. The others were given assignments to the European theater.

His first tour was in Okinawa where he served as a medic for his division. He told me this had less to do with “medical knowledge” and more to do with his inaccuracy as a marksman. Basically, his job was to recover the wounded, which was dangerous in its own right. He told me there was still gunfire to avoid and landmines to sidestep. Their time there lasted just a few months and they returned to the states in March of ’43. Their division did lose a few men. Luckily, my dad and Harold returned without injuries.

If anyone reading this a believer in fate, miracles or just “being in the right place at the right time,” what happens next will make complete sense to you. Waiting for them at the base in Medford, OR were invitations to audition for the band, as promised by the Sgt. Remarkable as it may seem, and not just to make a good story, he and Harold both made the band. As for the others, from what I was told, Bill and Dutch also became part of bands in Europe, but weren’t quite as active in theirs as my father had been.

Being part of the Division Band meant a release from their regular duties. Their focus now became rehearsals and preparation for traveling with some pretty note worthy celebrities, like Irving Berlin. My dad talked of their first “state-side” gig being at the Hollywood Canteen where they played for Doris Day.

Newspaper clipping sent to my grandmother in 1943.

Their new assignment didn’t save them completely from being sent back to the Pacific or from real military work. In the later part of ’43 they went back to Okinawa and began a tour, entertaining the troops while they still had to complete other duties, like KP (kitchen police) or MP (military police). They eventually made it to Leyte Island in the Philippines, just a bit before a general by the name of MacArthur returned.

Now how does this all really go back to the idea that music actually saved my dad’s life? Well, the division with whom he served was one of the first infantry divisions to land on the beach during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. They did much of the “mine sweeping” and securing of the beach so that MacArthur could make his grand entrance. As my dad told it, “It was a very bad day for the 96th.” More casualties occurred for this unit in just one day than had occurred in their other encounters combined.

While this part of the story admittedly caused my dad some guilt, he was also grateful that his reassignment to the band caused him to be held back for MP duty that day to “guard a general.” He truly believed he would have otherwise been within the number of dead or wounded that day.

A censored letter about their guard duty of General Bradley. Oct., 1944.

In the months that followed the band continued to play at service clubs to keep up morale and were part of small maneuvers until their return back to the states in August of ’45. In a letter to my grandmother my father looks forward to coming home and still playing music. He writes,” When this war ends we ought to be able to get a band together that will make the rest of the bands in town stand on their ears.”

- Letter to my grandmother from Bill Miller while in England, Aug., 1945

- My dad describing the band’s daily routine, Feb., 1944.

- My dad’s hope of getting the band together when they arrive home, May, 1945.

He told me of the Christmas of ’45 being the best of his life. This was the first that both Bills, Dutch, Harold, and Clem had all been together since the train ride to boot camp in ’42.

I’m grateful, too, that all of these men returned safely because I got to know most them as the guys in my basement, that is all except for Harold and Bill Miller. I only knew them from their letters, which my dad excitedly shared with me. Harold moved to Vegas to continue working in the music industry. He actually became part of the Tonight Show band and my dad would get occasional phone calls from him about the latest celebrity he met. Bill Miller moved to Brooklyn, NY and became a music teacher.

Bill Caton opened a music store in our town and taught me how to play the clarinet. It was in his store that I also took piano and guitar lessons. I remember Dutch being a quiet guy with thick glasses who never really said much. And then there was Clem, my favorite. He was tall and thin with dark wavy hair. He walked with a limp and I later found out it was a war injury, but that was all they would say about it. He always made sure the guys cleaned up their language when I was around and never forgot to bring me an orange “pop” when he came to our house.

The music that came from my basement were often jam sessions but mostly they were rehearsals for a real band called, “The Sammy Bill Orchestra.” My dad and the others played together in this band as well as the local Veterans of Foreign Wars band for many years. In my dad’s case it was literally until the day he died.

December 7, 1996 my dad came to my house more joyful than normal (he was one of the happiest people I knew). He had gotten a letter from his buddy “Caime.” This letter was special. Caime was a sax player in the band. My dad had not heard from him in over 20 years. He actually thought maybe he had passed. As he sat and shared that letter with me that morning he talked about the war more than he had in years. He told me again the story I just shared and reinforced how grateful he was for music. He said without it, I wouldn’t have been in his life. He was never very sentimental, but that day he was. He left my house with a kiss for me, both of my boys and even my dog. (He really loved that dog!)

My dad and Caime in Okinawa ’43

He was headed to a local hall to set up the equipment for his orchestra that was playing for a Christmas party that night. He was a stickler for making sure all the equipment was set up properly. When my phone rang a few hours later it was Clem asking me to meet him at the hospital. My dad had gone into cardiac arrest. As Clem told it, everything was set and he told my dad to come on and grab a bite before the job. My dad said he wanted get his “chops” warmed up a bit, but he’d be right there. He began going through his normal scales and such so Clem left the hall. Clem then told me, “In the 5 minutes it took me to realize I left my hat and walked back in to grab it, your dad was gone.” My dad was so blessed to have left this world in the company of his best pal doing what he loved. If only we all could be so lucky.

My, the beauty I now see in this creative process. These men didn’t care about time, space, money, or social pecking orders when then played. They played the music of their age and time because they loved it. It sustained them and gave them hope. They “jammed” to experiment with different genres in a safe place where there was no judgment from an audience. They allowed this form of media to permeate their lives, to “flow” through them. It just so happens that I was fortunate enough to catch some of the “overflow.”

Just a few more pictures to honor the boys!

[metaslider id=109]